Search this site

Announcing the Series Winners of the Emerging Photography Awards 2021

We’re delighted to announce the twelve winners of the 7th Annual Feature Shoot Emerging Photography Awards, with the selected artists spanning genres as well as continents. Christian K. Lee, Maggie Shannon, Jooeun Bae, Anouchka Renaud-Eck, Sandra Cattaneo Adorno, Daniela Constantini, J. Lester Feder, Michael Young, Matthew Barbarino, Rob Darby, Hanne Van Assche, and Horace Li will be featured in group exhibitions opening at BBA Gallery in Berlin on October 30th and at Studio Galerie B&B in Paris on November 7th.

This year, our series jury featured photographers, editors, and curators from organizations including TIME Magazine, Fortune, Rolling Stone, WIRED, The Guardian, The Dallas Morning News, The Cincinnati Enquirer, Paper Journal, GUP, and beyond. Thank you to Anna Goldwater Alexander, Marcia L. Allert, Diane Allford, Laylah Amatullah Barrayn, Lieve Beumer, Mia Diehl, Russell Frederick, Sarah Gilbert, Patricia Karallis, Sacha Lecca, Dilys Ng, Cara Owsley, Lauri Lyons, Danielle A. Scruggs, and Erik Vroons for their time and consideration of this year’s submissions. We’re honored to bring the work of these twelve winning photographers to Berlin and Paris.

The documentary photographer Christian K. Lee gives voice to Black gun owners in Armed Doesn’t Mean Dangerous, a series of portraits of people exercising their Second Amendment rights. “In the United States, gun ownership is a constitutional right; however, history shows us when African Americans assert these rights, they are infringed upon,” Lee writes.

“This fact was witnessed in 1967 with the introduction of the Mulford Act. It was a California bill that targeted members of the Black Panthers who were exercising their rights to open carry. In order to fully obtain the American Dream, I feel a deep passion to exercise all of the rights granted to me including my Second Amendment rights.”

Growing up in Chicago, the photographer saw harmful and negative portrayals of African American people with guns–depictions that ran contrary to his experience as the child of an Army veteran and police officer, and later, a gun owner himself. “The point of this project is to recondition myself, and others, toward the more positive view of Black people and guns: to promote a more balanced archive of images of African Americans with firearms by showing responsible gun owners — those who use these weapons for sport, hobby and protection,” he says.

Amid the lockdown that began in March of 2020, the photographer Maggie Shannon followed the work of midwives as they brought new babies into the world under an unprecedented set of circumstances. One midwife, Chemin Perez, moved her birth clinic to tents set up in a parking lot, while another, Jessica Diggs, transitioned to telehealth visits, showing parents how to listen to their babies’ heartbeats over video.

As hospitals filled, many women chose to give birth at home, with Shannon bearing witness to some of the most pivotal moments of their lives. “I was struck by the courage of every woman I witnessed: the calmness and resolve of the midwives and the power of the women in the throes of labor who pushed through all of the agony,” she writes.

“In the middle of a time of global suffering, there is a comfort in seeing each mother holding her new baby to her breast. Two humans touching for the first time, when touch is so severely restricted. At a time marked by separation and death, these stories of connection, care, and birth feel especially healing.”

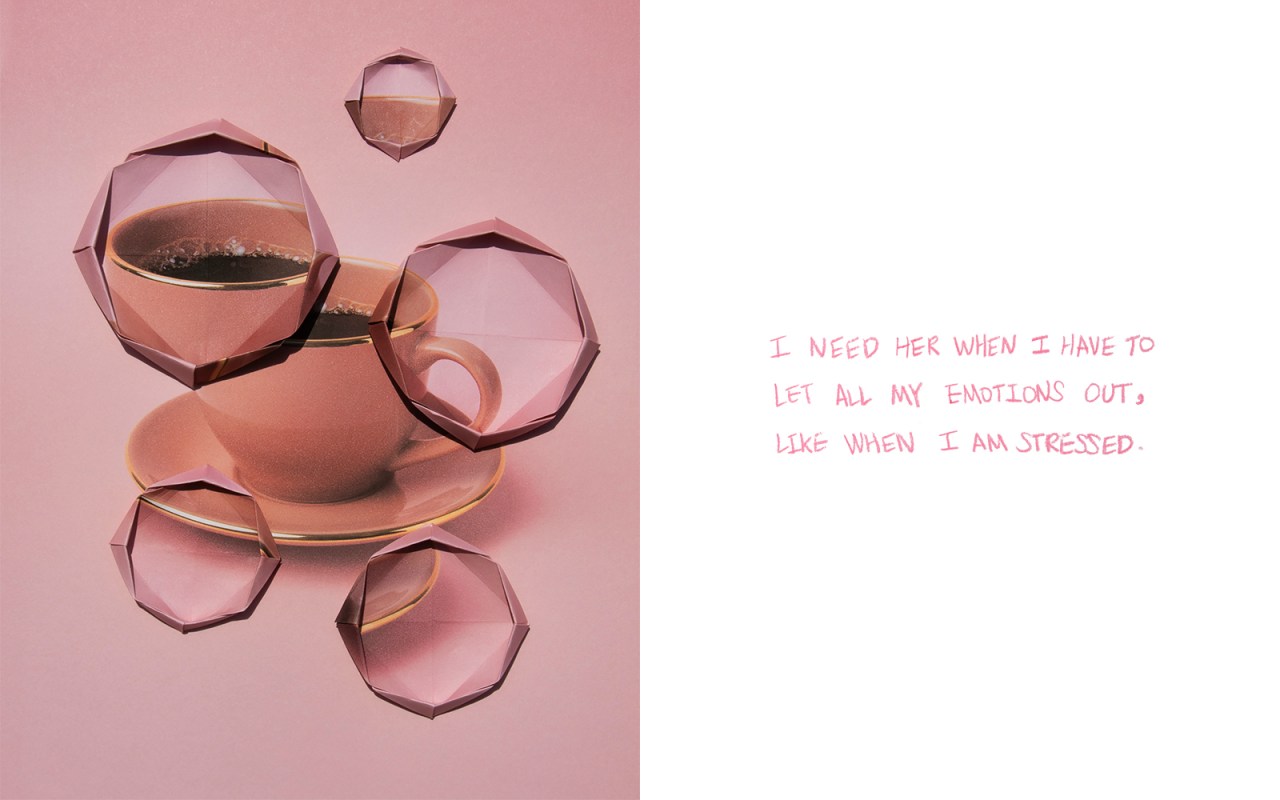

For her collage series Mono-, the photographer Jooeun Bae found inspiration in an ordinary breakfast. While she usually eats with family, this time she was alone and had time to reflect on the everyday beauty of the objects that surrounded her: a coffee cup, utensils, a plate, and so on. The revelation that she’d taken the individuality of these items for granted sparked the understanding that we all do something similar with the people who inhabit our daily lives.

“I use 30 everyday objects as a metaphor of 30 people that I often undervalue […] merely because I have gotten comfortable with having them around,” she writes. “Thus, I photograph each item with just a solid colored background to simply capture them as they are. The series reveals each object’s individuality and uniqueness by using handmade collages, unlike the usual images that can be reproduced.” Each piece is one of a kind.

Anouchka Renaud-Eck‘s long-term project Ardhanarishvara – In Search of Union is an exploration of love, marriage, and the search for a partner, as experienced by many young people in India. “In Hindu mythology, Ardhanarishvara is one of Shiva’s forms in which he appears with his wife Parvati together as one body,” the photographer writes.

“From a rite of passage to adulthood to an alliance between two families, the wedding is a prominent event for everyone involved in it. Although traditions may vary from region to region and between different religions, the search for the wedding partner by the parents remains the same.

“In the wedding market, women have their best chances to get married from the age of 18 to 25, while for men their best chances are from the age of 21 to 29. After these ages, it becomes almost impossible to find a partner. This matrimonial quest is therefore a countdown for young people who try to forget their teenage love in order to honor their parents’ choice.

“Hindu cosmology presents several male/female pairs that are inseparable. The mythology tells many divine love stories that have a similar outline: union, separation, and reunion. This pattern is very similar to love stories told through the centuries of story-telling. Asking us the question: can there be no love without pain?”

Águas de Ouro tells the story of Sandra Cattaneo Adorno‘s return to Ipanema Beach, where she spent much of her childhood. The project, whose title means “waters of gold”, is a celebration of the shimmering sunlight of Rio de Janeiro and the many people who find hope and joy on the shores of the beach. “I remember the sun, the dazzling light over the sea,” she writes. “And the people, gentle figures moving slowly across the sand.

“Going to the beach as a little girl was different then; we weren’t allowed in the sun. To my British mother, the sun was alien, unsafe, harmful, even. It would burn our light skin. But I could look. And take in that light and feel the lightheaded dizziness of the sea and the people, the elegant people of Ipanema, swaying with grace as if they were dancing at the tempo of bossa nova.”

The photographer Daniela Constantini pays homage to the women who helped shape her in a series of rich and evocative portraits that symbolically span generations. “[This series] is an ode to women,” she says. “To the women in my life, whom I met since I moved to Bern and have now become family, close friends, or new acquaintances, muses to my work.

“Women in my family have always been strong figures, hard workers, feral, outspoken, pillars to the family. I became a photographer when most of the women I looked up to and grew up with were no longer in this world. I decided to honor the women of my past by honoring the women in my present. I occasionally include garments or pieces that belonged to my grandmother, great aunt, and great grandmother. This work balances past and present, desire, and memories.”

J. Lester Feder, a writer, photographer, and historian, traces the legacy of dance in Detroit. “Detroit-style ballroom dancing was invented in Black clubs during the Jazz Age, reinvented for Motown, and has been kept alive by dancers in their 60s, 70s, and 80s,” he writes. “But the whole scene was threatened when COVID hit, shuttering ballroom clubs and killing dozens of Detroit’s most experience dancers. This project documents the ballroom scene trying to recover as Detroit re-opens.”

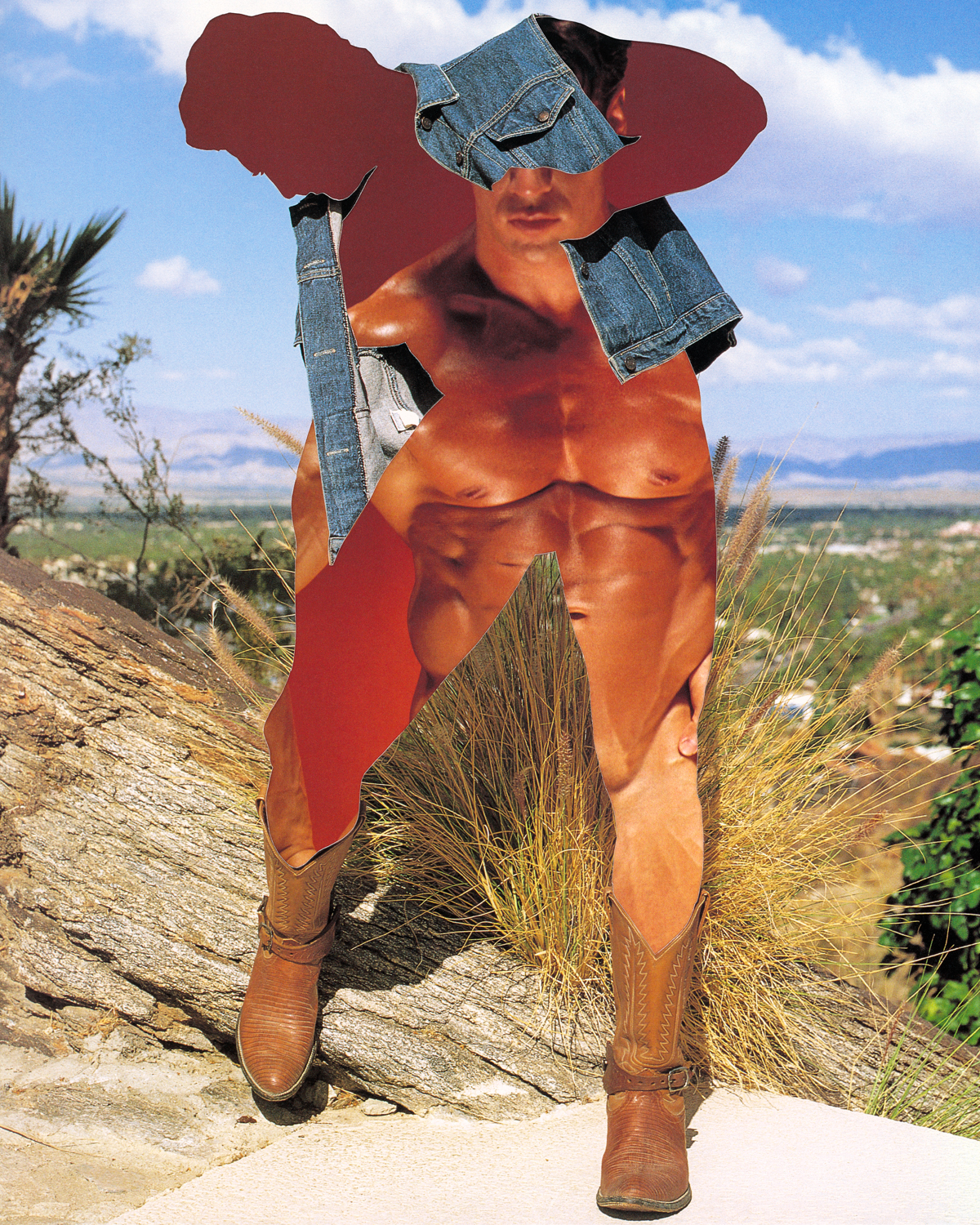

The lens-based artist Michael Young uses images found in vintage gay pornography calendars to create Hidden Glances. The original calendars were published during what the artist calls his “lost years” (that is, “from when I was beginning to recognize my sexuality as a youth until I came out in 2000”). To create the final images, he’s hand-cut and layered the originals before re-photographing them.

“By eliminating the presence of exposed skin in the top layer, one muscular silhouette becomes a window that both reveals and conceals parts of another month’s figure,” Young writes. “The use of calendars is strategic; they chronicle and mark time. In my case, they represent a long period in my life when others assumed I was straight, or I was told that being gay was wrong and being heterosexual was the only acceptable way to be.

“Ironically, the men in these calendars portray sexualized (for that time period) heterosexual archetypes that many in the gay community had appropriated. These ‘manly’ men that society was trying to train me to become ultimately became the men I longed to look at and galvanized my true identity.

“In essence, the work becomes a visual compression of those years when I wanted to look at other guys but could only risk taking quick glimpses because I was afraid that my gaze would linger too long and my homosexuality exposed.”

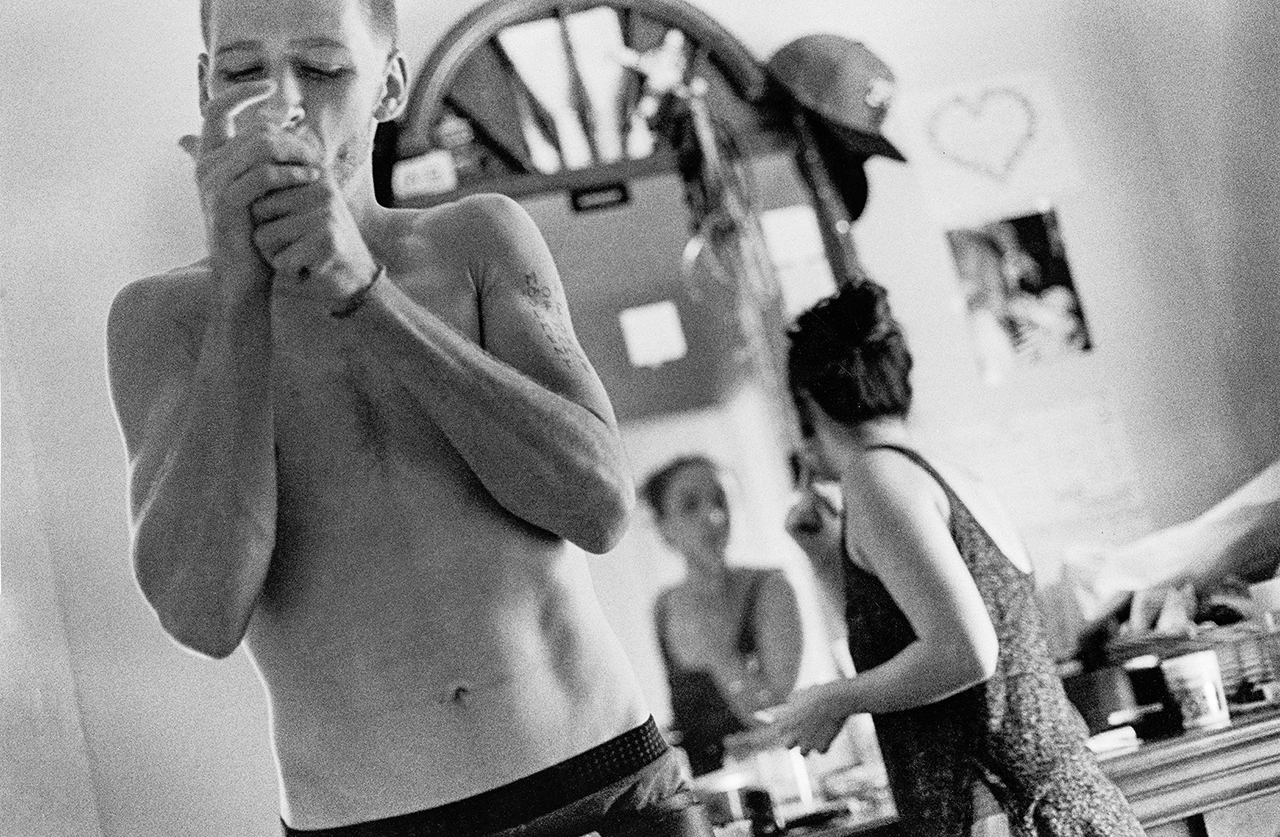

In Graceland, the photographer Matthew Barbarino returns to his hometown outside of Binghamton, New York, a community hard hit by the opioid epidemic. “By age 16, the heroin epidemic was a very real issue in my circle of friends, and coming to terms with it has not only been the focal point of my life but an ongoing source of inspiration for my work,” the artist says. The project is his portrait of a place that helped shape him.

“Binghamton is not unique,” Barbarino has written. “It is one of many small American towns currently dealing with the exodus of industry, economic decline, and rampant heroin addiction. Many photographers may come into places like this from somewhere else, hoping to gain understanding, or a glimpse into an unfamiliar world.

“But my project is not about someone else’s town, it is about my home. The people in the pictures are not random subjects, but my lifelong friends. The project is not an attempt to understand someone else’s world, it is an attempt to understand myself, to learn who I am and where I come from and how to orient myself in a new world.”

Rob Darby‘s interest in weather started in childhood. “I began shooting when I was very young, using a Brownie camera to photograph and catalog cloud types,” he remembers. “I picked up photography again in earnest in 2005 coinciding with a newfound passion for chasing storms. My work has evolved into less literal and more abstract landscapes.”

Beyond capturing the beauty of nature, Darby is interested in the emotional truths that can be discovered in extreme weather or stormy skies. His winning series is monochrome, created while he was chasing storms in Kansas.

The documentary photographer Hanne Van Assche transports us to Udachny, a mining town in the far East of Russia, in her series Udachny – Lucky. “It is located in Yakutia, a remote region captured in the icy grip of winter most of the year,” she writes. “A frozen world of dense taiga and immense tundra zones and hardy pine trees. Few people choose to live here, but those who do are proud citizens.

“Yakutia is known as the treasury of Russia. It is one of the world’s richest regions in natural resources. According to Siberian legend, God once spilled a bag of earthly treasures over this part of the country. A thick layer of permafrost covers large reserves of coal, gas, gold and–diamonds.

In 1955, geologists discovered a diamond deposit in the area; it was turned into an open-pit mine, overseen by Alrosa, a Russian company. “Today, the 12,000 inhabitants of this town are still connected via the mine,” Van Assche explains. “Alrosa expects Udachny’s production to last for at least another 25 years and continues to facilitate the lives of its workers.

“Even though a steady job seems to be the only motivation to live in this monotown, residents find more reasons to stay, often related to the strong connection they experience with nature and their fellow citizens. Isolated from the rest of Russia, Udachny truly feels like a world on its own. The hospitality and optimism of the inhabitants soothe the harsh climate.”

“2020 is finally over, and no one will miss it,” the photographer Horace Li, who was born in China and is based in Sydney, writes in the statement for his series The Journey Home. Made during the pandemic, the project brings to life the Chinese family tradition of reuniting during the Chinese New Year, even amid lockdowns and travel restrictions. The idea behind the series: “Since we can’t go home, we will bring home here!”

“I brought a ‘Siheyuan’ (a historical type of Chinese residence) backdrop to the studio and built a symbolic home of the Chinese people’s,” the artist says. “During this Chinese New Year, I invited the people from the Chinese community in Sydney to come to take a family portrait. Whilst being overseas, they can still have a journey home, in the way I am best at, documenting the stories of those Chinese families during this special period. There are homesickness, regrets, helplessness in the stories, but there will be warmth. All these will eventually become how we remember the Year of the Ox.”