Search this site

Surreal Photography: 30 Artists Create Uncanny Dream Worlds

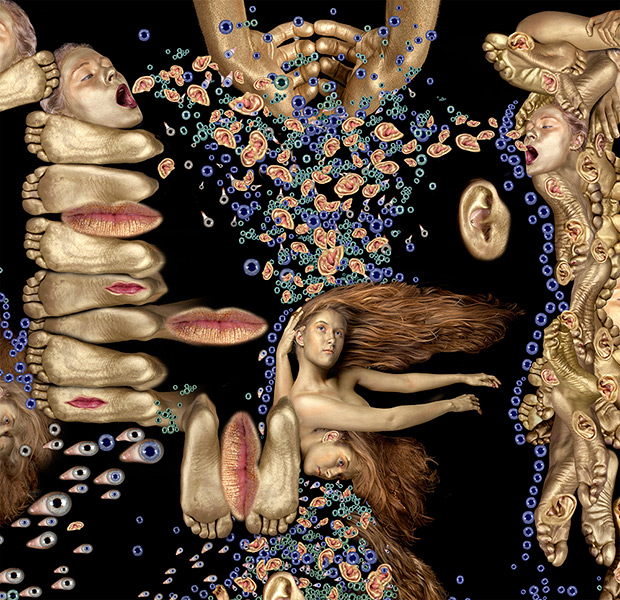

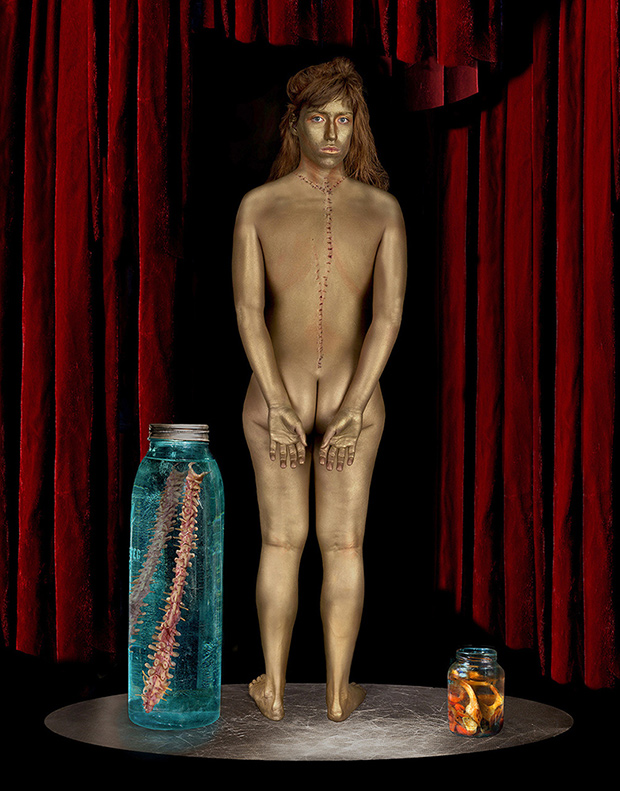

The photographer Lou Krueger died—that is, his heart stopped—and he came back to life. during that time, he heard voices. They told him, “Go back. We’re not ready for you yet.” In the aftermath of experiencing cardiac death, he’d go on to create The Temple of Wonders, a surreal photography series that explores the strangeness, beauty, and fragility of the human body. Using photomontages to envision the impossible, he spent up to two years realizing some of the final images.

Since André Breton’s published the Manifesto of Surrealism in 1924, our understanding of surrealist photography has evolved. To start, the elaborate darkroom techniques used by the likes of Man Ray and Lee Miller (polarization, montage, and double exposure, to name a few) have been joined by seamless digital compositing, thanks to tools like Photoshop.

But the basics have remained the same: the term “surreal photography” describes work that stems not from rational thought but from the unconscious realm of dreams and imagination.

In some cases, the subject matter might be inherently surreal; for example, in the 1960s, Arthur Tress physically recreated nightmares experienced and retold to him by children. In others, the technique itself could be surreal; double exposures and photograms both speak to the history of the genre.

While exploring the stories we’ve published on surreal photography, I noticed a recurring theme: a life-altering event inspired many of these artists to turn their attention away from reality and venture fearlessly into the murky unknown. It’s certainly not a rule, but it is an idea that emerges again and again. Lou Krueger’s work is one example.

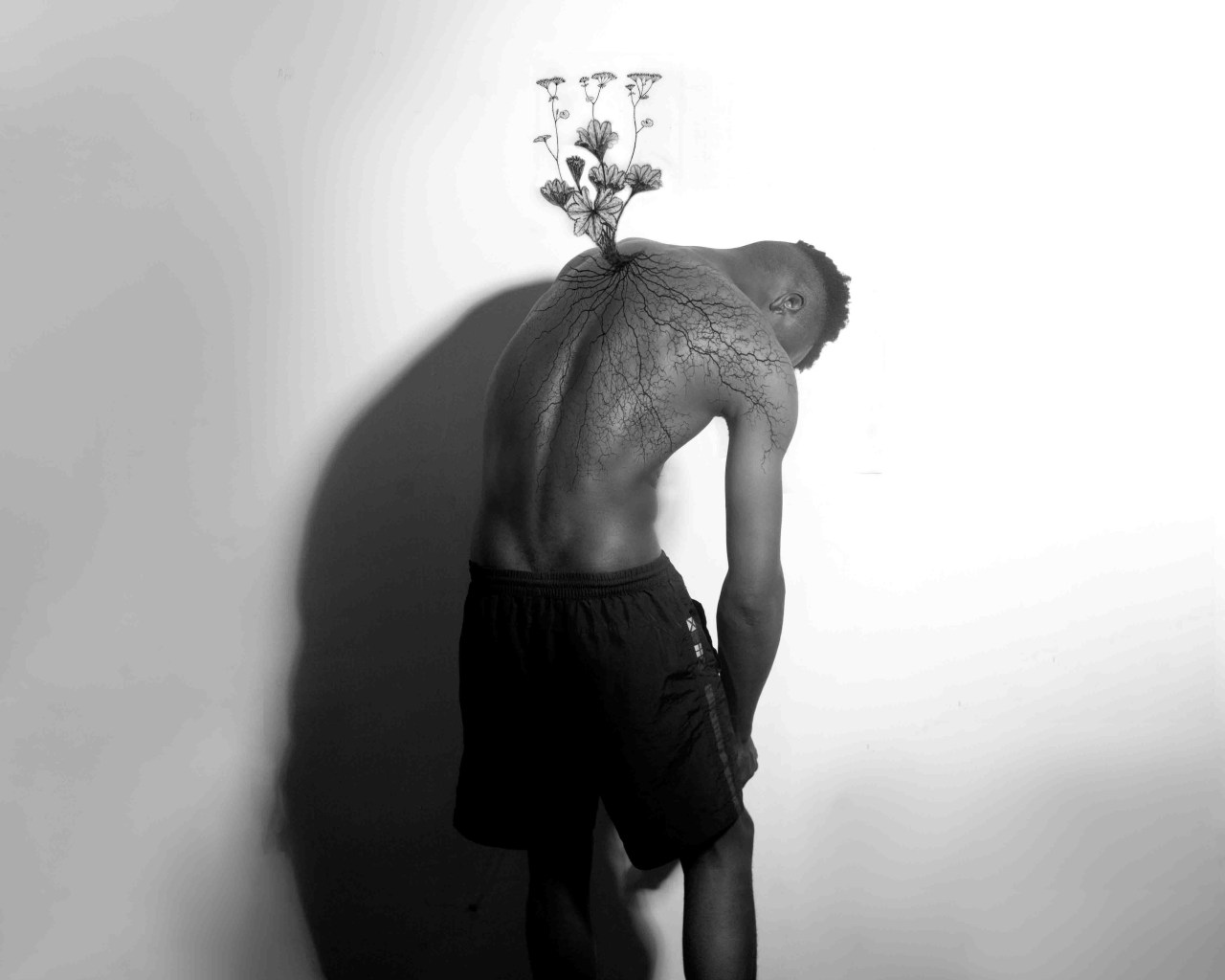

Bade Fuwa, meanwhile, made haunting and mysterious photographs while grieving the death of his mother; the act of creation became a kind of escape from pain. For his part, Karen Khachaturov was motivated to collaborate with his grandfather after learning he had been diagnosed with cancer; together, they created a fantasy world all their own.

For that reason, surreal photography stories are often not only the most mysterious but also some of the most personal, with hidden traces of the artist waiting to be discovered at every turn.

After Coming Back From the Dead, This Photographer Created Astonishing Images

Lou Krueger kicks off our collection of surreal photography. He is not a religious man, but his brush with death, followed by a diagnosis of and treatment for epilepsy, has instilled within him a persistent consciousness of the failings and fragilities of the human body. Every element in these montages is shot by Krueger himself.

His models and props are adorned with either gold spray paint or airbrush makeup, though most of the models’ bodies are painted by hand. The shooting sessions consume hours and are exhausting for everyone involved, but the process is in many ways a labor of love. As for post-processing and compiling the montages, Krueger has devoted hundreds upon hundreds of hours.

Surreal Photography Helps An Artist Cope During a Time of Grief

Following the death of his mother, Bade Fuwa experienced all-consuming grief. Photography became a channel for expressing that pain, and at the same time, it became an escape.

“Since I found photography, I know I can never let it go,” he tells us. “Through photography, I’ve found a kind of calm that nothing has given me before. It’s more than photography to me; it’s my life. It’s almost like something my mother sent to me.”

Jerry Uelsmann, The Artist Who Turned Photography Upside Down

Moa Petersén’s new book Eighth Day Wonder is a biography of her friend, Jerry Uelsmann, the man who pioneered the art of darkroom experimentation. By “breaking the rules” established by those who came before him, Uelsmann helped redefine what photography could be. In stark contrast to the purist ideals of the time (the 1960s), his work didn’t capture an external reality but expressed an internal vision.

Surreal Photography Inspired by the Nightmares of Children

While working with the educator Richard Lewis of The Touchstone Center, Arthur Tress observed an exercise in which young people were asked to construct poems and paintings of their dreams. Inspired, he began collaborating with children to create haunting silver gelatin photographs. Influenced in part by the concept of Jungian archetypes, the images represent both the anxieties of the individual and the collective dread of the 1960s, the decade in which the images were made.

Finding Humor In Life’s (Many) Challenges

In her series Locked-In, Susan Borowitz poses for absurd and humorous self-portraits that visualize the frustrations and roadblocks of everyday life. She says she was subconsciously inspired by her own past experiences with clinical depression.

Fantastical Photos Take Us Inside a Photographer’s Imagination

When spending time with Aaron Ricketts‘s work, the influence of the Surrealists is unmistakable. His fondness for hats, for instance, mirrors the painter René Magritte’s enduring fascination with bowler hats.

A photographer from the age of sixteen, Ricketts uses the camera not to capture the world around him so much as the world inside his head; through compositing and photomanipulation, he’s created a dreamscape where anything is possible and reality is merely a suggestion.

One Man Photographs His Grandfather’s Battle with Cancer

Gary became his grandson Karen Khachaturov‘s muse the day he learned had bladder cancer. “He was diagnosed in 2017,” the Armenian photographer remembers. “It was pretty shocking for everyone.” Over the span of a month, the two of them worked together to create a series of playful and uncanny images, with Gary in the starring role.

Despite the shock, or perhaps because of it, Khachaturov and his grandfather immersed themselves in a candy-coated dream world of their creation. “The images were taken in my studio, and all the items were created by me,” the photographer explains. “I painted the walls and made costumes for him.”

Bewitching Photographs Harken Back to Childhood Wonder

In Mythos, Tami Bone pays homage to her childhood self and returns to her earliest memories. The images are montages composed of an average of five to seven exposures; one image requires weeks, usually a month, to complete. “It always has something to do with seeing the unseeable, knowing the unknowable, with a keen awareness that there’s so much more than any of us will probably ever see,” the artist tells us.

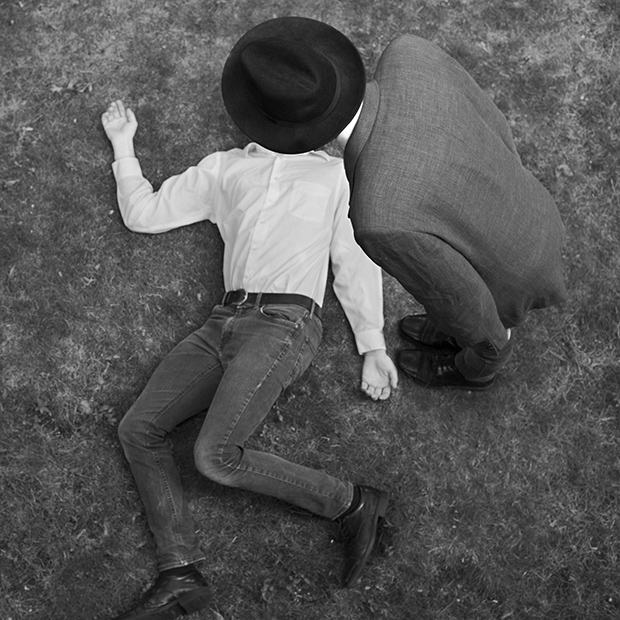

In a Time of Mourning, One Photographer Turns to His Young Son

Following the death of his grandmother, the photographer Troy Colby and his son started creating pictures together. In mourning, they carved out a world that could exist for just the two of them, a realm of make-believe where time strayed from its linear path and where magic reigned over mortality. Out of the wreckage of that winter, they eventually emerged.

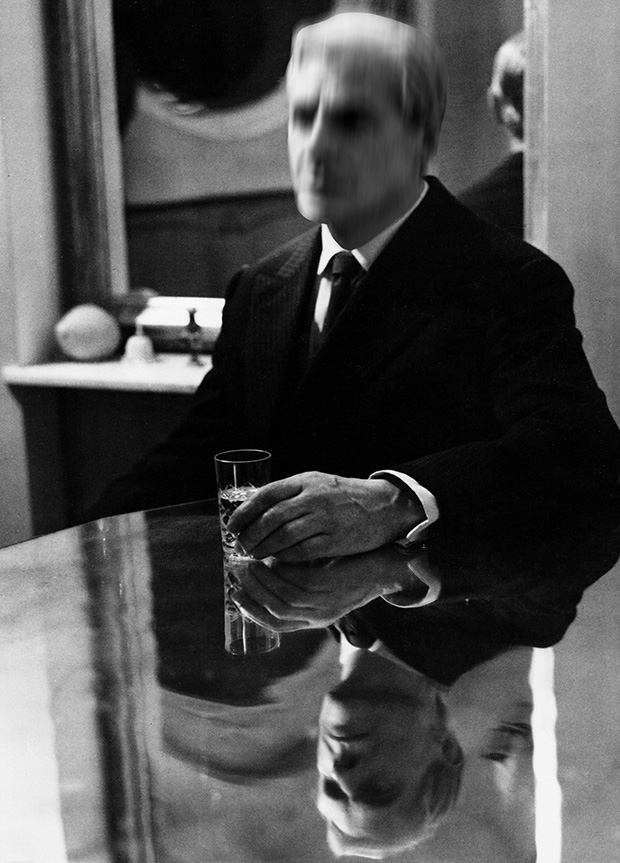

Choreographed Visions of Faceless Figures in Suits

When creating this series, the photographer Ben Zank was also inspired, in part, by the painter René Magritte. (He incorporated some of those references as well, including a wide-brimmed hat and bicycle. “Each image is its own little novel, but I’ll never officially attach a meaning to it,” he explains. “I’m fine with people coming to their own opinions. It makes things more fun.”

Surreal Interpretations of Womanhood Photographed by Marjorie Salvaterra

In these uncanny images, the photographer Marjorie Salvaterra gathered friends and cast them as anonymous “everywomen.” Drawing from art historical references and her own life, she creates images that are at once amusing and unsettling.

Photos of the Darkness Inside a Child’s Imagination

While creating these photographs, Stavros Stamatiou stepped back into the abyss of his childhood memories, wandering alone in the night throughout the ancient Grecian land beside his home. All that was once familiar during the day became supernatural at night, and he surrendered to whatever it was that lingered in wait behind the veil of his imagination.

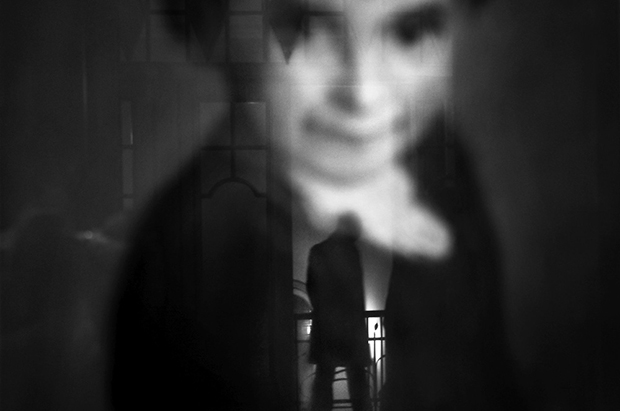

Ghosts of the Past Appear in These Haunting Images

“All the people in these pictures are strangers from the past, most probably dead,” the photographer Frank Machalowski says. This project originated in a flea market, where the artist discovered a treasure trove of old photographs. From there, he merged those old photographs with new images he created using a custom anamorphic pinhole camera. In the resulting pictures, the past and present collide.

The Funny, Scary World of One Young Photographer

The Japanese photographer Izumi Miyazaki, like each of her pictures, is a bit of a mystery. She photographs herself, but the self-portraits aren’t actually about her. In the world of Miyazaki’s alter ego, we enter a realm of contradictions, chaos, and magic.

Eerie, Dreamlike Moments Made on Light-Sensitive Paper

In these playful, nostalgic images, Vanessa Marsh returned to the darkroom, the old stomping ground of the Surrealists. Her process involves carefully setting her own acetate drawings on top of photographic paper and exposing them to light for precise periods of time. She removes and replaces elements at just the right moment to create a make-believe “foreground” and “background” in an entirely two-dimensional world.

A 91-Year-Old Woman Embraces Life in Profound and Playful Images

Tony Luciani’s collaboration with his mother, then age 91, inspired both of them to return to the world of make-believe. The photographs together contain several well-known motifs among Surrealists, including mirror images and shadowplay. At the same time, they speak to the idea of memory and the power of the imagination.

Gravity-Defying, Surreal Photography Brought to You By ‘Mikes Butt’

When creating his playful compositions, Mike Dempsey (aka Mikes Butt) draws inspiration from his love of skating. “I love images where you can see gravity, like when a car is about to burst through a fence off a bridge or when an old lady is dropping a cake down stairs,” he explains. “I like the point of no return that makes the audience predict where they subject goes next.”

Ziqian Liu Creates Fragmented Images of the Self in Her Surreal Photography

Looking through Ziqian Liu‘s soft and ethereal self-portraits evokes memories of Florence Henri, the so-called “queen of surrealist photography,” who also used mirrors and flowers in her reality-distorting compositions. “The reflection of the mirror expresses the fusion of the reality and the world in my mind,” Liu says.

A Surrealist Daydream Made From Stock Photos

The photographer Weronika Gesicka spent hours pouring through pictures archived in image banks, with most dating back to the 1950s and ’60s. In Photoshop, she tore these old images apart and then put them back together, like pieces in a jigsaw puzzle gone wrong.

Parental Guidance: Vibrant, Surreal Portraits Made During Lockdown

“Someone recently asked me if I took a bunch of LSD with my parents and watched a lot of Wes Anderson movies [to make these photographs],” the Irish photographer Enda Burke recalls. Homebound With My Parents is a collaborative project made during an inherently surreal time in recent history, using punchy colors and absurdist humor to transform mundane moments into dreamlike ones.

Introducing America as You’ve Never Seen It Before

Inspired by science fiction, Aydin Büyüktas spent a month traveling 10,000 across the US, capturing the landscape from mind-bending angles with help from a drone. His composites took twice as long to create: each one is made up of eighteen to twenty individual images.

Photos of Cloned Individuals Depict the ‘Power of Theater in a Still Image’

In his series Monodramatic, the photographer Daisuke Takakura explores the idea of selfhood by cloning many versions of the same actor and character within a single image. The final images are seamless composites that are at once playful and uncanny.

Whimsical Tableaux Set in the World’s Most Beautiful Landscapes

The artist Simple-T creates her surreal photography by dressing in masks and costumes. From there, she uses the landscapes of Iceland, California, Jordan, and beyond as stage sets for her uncanny tableaux.

Surreal Polaroids of Iceland by Paul Hoi

In the work of Paul Hoi, it’s more the technique itself than the content of the photographs that verges into the territory of Surrealism. Using expired Polaroid film, he transforms the landscape of Iceland—already a somewhat surreal location—into scenes so strange they seem to have been plucked from a dream.

Japanese Photographer Creates Surreal Scenes of Anonymous Girls

In these photographs by Osamu Yokonami, girls dressed in identical outfits create strange and mysterious tableaux, transforming picturesque landscapes into stage sets and playgrounds.

‘Lady Things’: Surreal Portraits of Femininity

In her series Lady Things, the photographer Robyn Cumming creates surreal portraits of femininity, replacing the heads and faces of her subjects with soft, delicate objects. Against quaint patterned wallpapers, frilly curtains, or ominous blackness, the stiffly posed figures are veiled like strange brides in flower petals, luxurious fabrics, and a flock of doves. Though observably of varying ages, the women become uncannily interchangeable with one another.

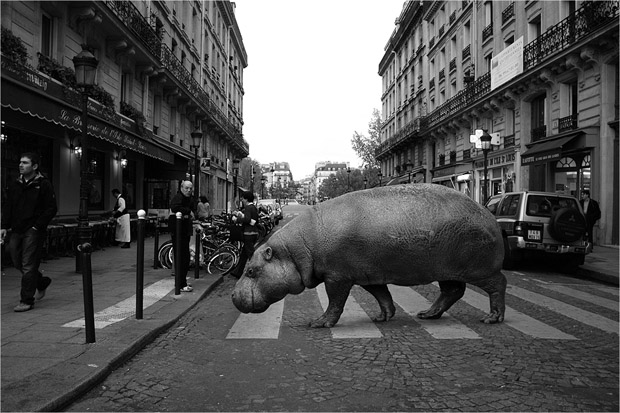

Wild Animals Roam City Streets in These Surreal Photos

In the surreal photography of Ceslovas Cesnakevicius, wild animals roam free throughout the city: penguins emerge from the subway, hippos cross the street, and giraffes navigate sidewalks.

Rare Phobias Come to Life in Disturbing Collages

If David Delruelle‘s collages have an Alfred Hitchock/Rod Serling vibe to them, it’s not only because of the chosen subject. The pictures are made using archived imagery from the 1950s and 1960s. While creating these images—each inspired by a diagnosable phobia—the artist was consumed by the project and stayed up nights pouring over vintage images and dreaming up surreal scenarios in Photoshop.

A Portal Into Another World Through Puddles on the Street

A period of depression inspired the photographer Dr. Joshua Sariñana to embark on Surface and Consciousness, a series of images made from the reflections formed by puddles on the street. “I like to think of these puddles as entryways into another dimension,” he says. “If we could jump through them, then we would be turned upside down and land into another dimension.”

Enigmatic Self-Portraits by ‘A Girl Who Tried to Disappear’

Viktória Kollerová is an artist unafraid to dive headlong into the murky and often painful corners of the human psyche. She shoots in black and white, and her primary subject is her own body. She finds ambiguous, impenetrable locations in various states of decay and weaves through them like a serpent.

Like the artist’s physical figure, the meanings of Kollerová’s portraits are shifty and fugacious. In many ways, she’s leading us down with her into the dungeons of our own minds, whispering something inaudible, and leaving us there in darkness.

Read this next…

Surreal Photography: 12 Creative Techniques to Try