Search this site

Looking back at LGBTQ life, 50 years after Stonewall

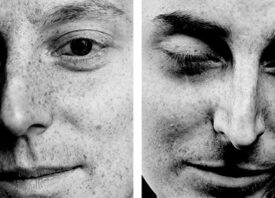

KARLA JAY, born in Brooklyn in 1947, is a distinguished professor emerita at Pace University, where she taught English and directed the women’s and gender studies program between 1974 and 2009. A pioneer in the field of lesbian and gay studies, she is widely published.

CHELLA MAN is a 20-year-old, deaf, genderqueer, queer artist currently transitioning on testosterone. “Every day left me exhausted as I performed traditional femininity.” Born in Pennsylvania, he moved to New York to study virtual reality programming at The New School, while creating art on the side. His main focus is to educate others on issues regarding being queer and disabled within a safe space.

Fifty years after the Stonewall Rebellion gave birth to the global LGBTQ Movement, generations have continued the fight for freedom and equality — knowing full well the moment we stop fighting is the moment that all hell breaks loose.

Consider the June 28 report of a Black trans woman who disrupted a drag show at the Stonewall Inn during the 50th anniversary celebration to call out how Pride has been co-opted by corporations even through Black trans women are being murdered — and was threatened with police action in an effort to silence her.

It was a cruel but telling episode of history repeating itself, half a century later at the very place where Gay Liberation began. In the early morning hours of June 28, 1969, by homeless LGBTQ teens, trans women of color, lesbians, drag queens, and gay men stood up against a police raid, sparking off a multi-night uprising on the streets of New York’s Greenwich Village.

In the aftermath of Stonewall, hundreds of new LGBTQ civil rights organizations took root across the country and around the world, forcing the U.S. government to change their laws. Though the war has not been won, the battles rage on.

Collier Schorr: Stonewall at 50, currently on view at the Alice Austen House in Staten Island, New York, through September 30, honors those doing the work in a series 15 black and white portraits of intergenerational activists including native New Yorker Karla Jay, an early member of the Gay Liberation Front (GLF) and the Radicalesbians who famously incited the “Lavender Menace Zap” at the Second Congress to Unite Women in 1970.

Here Jay shares her memories and lessons gleaned on the front lines, which we can use to continue to fight in the name of those who did not make it out alive.

ACHEBE POWELL, born in 1940, was raised in Florida, graduated with a B.A. from The College of St. Catherine and an M.A. from Fordham University, and has resided in New York City for the past 40 years.

Can you take us back to the summer of 1969 and describe what the energy was like before and after the Stonewall Riots?

“There were so many things happening in 1969. The Civil Rights Movement and the Women’s Movement were quite active. Later that summer was Woodstock and the first man on the moon. It was the Age of Aquarius.

“Stonewall, particularly GLF came along in this age of rebellion against social norms. We were very androgynous in the GLF. Those kinds of ideals and the ways we tried to transform the world in the wake of the Stonewall Uprising has been somewhat erased. You can see this kind of individualism that is irrespective of the sex assigned at birth.”

“The older gay organizations wanted us to be like everyone else and they tried to enforce that with a dress code at the demonstrations. When they had Remembrance Day on July 4 at the Liberty Bell, men had to wear suits and ties and women had to wear a dress or a skirt.

“The radicals in the GLF said, ‘No, we don’t want to do that. Why are we trying to ape heterosexuals? Marriage hasn’t worked so well for them. Monogamy hasn’t worked so well for them.’”

EILEEN MYLES was born in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and was educated at the University of Massachusetts-Boston. They moved to New York City in 1974 to be a poet, and subsequently a novelist and art journalist. They gravitated to the St. Mark’s Poetry Project, where they studied with Ted Berrigan, Alice Notley, Paul Violi, and Bill Zavatsky. From 1984 to 1986 Eileen was the artistic director of St. Mark’s Poetry Project.

What was it was like to join the Gay Liberation Front in its early days?

“Many members of the GLF started to live in collectives and came out quite strongly against monogamy and these patriarchal relationships, which seem to be tied to property rights. We were rejecting that and wanted people to be able to live freely. One of our slogans was, ‘We will never go straight until you go gay.’

“By this we meant we weren’t going to change. We wanted society to be queerer and to give up this idea of going two by two into the ark along with the animals. We felt it was an incorrect model.

“I still strongly believe that has the other model of LGBT organization, which came out of the Gay Activist Alliance, which split from the GLF in December 1969 and went on to become a one-issue group. The GLA were only interested in LGBT rights, unlike GLF, which was very intersectional; we were hooking up with the Black Panthers and so on. I think if this radical vision had prevailed, rather than going into making small incremental changes in legislation. We wanted decriminalization not legislation.

“Instead of legalizing certain relationships, we need to allow everyone to have a person of choice be the other and not to define what that could be. It could be a lover, a neighbor, any relative, any person you want to be there for you and to have the right to inherit, to be there for you in the hospital.

“We were thinking this way 50 years ago and if we hadn’t conceived of communal relationships in the ‘60s, we wouldn’t have been able to take care of the men and women who had HIV in the ‘80s. To take care of such people took a village. It took shifts and shifts of people to look after them. That’s a reflection of the communal way of thinking and that’s why the lesbians from the 1960s played such an integral part. We understood communal activity, everything from potluck to communal living.”

ZACKARY DRUCKER is a transgender performance artist who breaks down the way we think about gender, sexuality and seeing. The artist uses a female pronoun, and through her participatory pieces she complicates established binaries of viewer and subject, insider and outsider, and male and female in order to create a complex image of the self.

What was the impetus to join the Radicalesbians?

“The feminist movement was not welcoming of lesbians. Betty Friedan had called us on numerous occasions a ‘lavender menace.’ She said that if people knew there were lesbians, we would destroy the Women’s Movement.

“On Match 15, 1970, Susan Brownmiller published the first major piece in the New York Times Magazine [“Sisterhood is Powerful”] about the Women’s Movement and she dismissed this and said we were a ‘lavender herring’ with no clear and present danger, that we were just this false clue — and that was even more insulting than being called a menace. Making up t-shirts that aid ‘lavender herring’ was really unappealing, although that did happen but it just didn’t work.

“We started to plan a takeover of the women’s movement on March 1, 1970, at a conference called the Second Congress to Unite Women in the Village. In order to tell the feminists how we felt, we as a group wrote a document called ‘The Woman Identified Woman,’ which is one of the classic documents of the 1960s and ‘70s.

“It starts out: “What is a lesbian? A lesbian is the rage of all women condensed to the point of explosion.” It was such a powerful document and we all put our two cents in. There were about 20 of us who worked on this and a woman named Artemis March collated it.

“We tie-dyed ‘Lavender Menace’ t-shirts. We made up placards that said things like, ‘Women’s Liberation is a Lesbian Plot,’ ‘Take a Lesbian to Lunch,’ and ‘We Are Your Worst Nightmare. We Are Your Best Fantasy.’ It was a zap and you wanted a humorous element so that they wouldn’t call the police and have you arrested. If people were laughing, you were less likely to be arrested and that’s why we tried to inject humor into the zap.”

MARTIN BOYCE was at the Stonewall on the night of June 28, 1969. “The only place we had to go was Christopher Street,” Mr. Boyce, now 70 and a chef living in the Yorkville neighborhood of Manhattan, told the New York Times in an interview.

Could you share your memories of the Lavender Menace Action?

“The morning of May 1, we gathered outside PS 41 on West 11 Street. We had two women behind the stage and when the Congress started they cut the lights in the auditorium and when the lights came back on, the audience was completely surrounded by lesbians. We had 40 women in the aisles. They were saying, ‘Here we are. We are the Lavender Menace. You can’t ignore us. Look how many we are,’ and they were chanting ‘Join us! Join us!’

“I went in ahead of them in regular clothing and was planted in the audience. I stood up and said, ‘I’m tired of being in the closet of this movement!’ and I ripped my blouse off. Underneath I had a Lavender Menace t-shirt on, and I went out into the aisle and I joined them.

“We all went on the stage and said, ‘You can’t go on in this movement and not address the issue of lesbianism.’ This two-day congress didn’t have a single workshop or speaker that was going to address lesbianism, class, or race. We told them in no uncertain terms that this was unacceptable and they had to address all three.

“How could they get up there and speak as if we were all middle-class white women? They did. They changed the Congress and many workshops were added. Lesbianism was put on the agenda of the Women’s Movement and it never came off again. Except, as a footnote, Betty Friedan herself did not accept lesbians into NOW as full participants until 1977 after pressure from the Congress of Women in Houston in 1977. They told Betty she had to do this and she finally did.”

GREGG BORDOWITZ Since the late 1980s, writer, artist, and activist Gregg Bordowitz has made diverse works—essays, poems, performances, drawings, sculpture, and videos—that explore his Jewish, gay, and bisexual identities within the context of the ongoing AIDS crisis.

What is it like to look back 50 years later at this historic event, in light of all the changes that have occurred?

“There are many lessons to activism that young people can learn from. Pat Schroeder, a Senator, famously said, ‘You can’t roll up your sleeves and wring your hands at the same time.’ If you’re an activist, you’re not going to be sitting home watching or listening to news and being depressed about it. You will be out there.

“There are three things I think at are really important. One: we had a lot of fun. One of the reasons the story of the Lavender Menace Action is so famous is because we had so much fun doing these actions.

“Secondly: you will have friends for life. The people I got together with and took risks with 50 years ago are my friends today. If you don’t find something you love to death, you’re going to have less of a life,. You have to have passion to go on.

“Third: you have to be in it for the long haul. You can’t be discouraged by setbacks. We have to get this horrible backwards person out of the White House and that’s goal number one, and then we can work on getting more things.

“Who profits from activism? The activist. I always thought I went in it for other people, but who got the most out of this? Me.”

KARLA JAY

All images: © Collier Schorr, courtesy of the Alice Austen House